Mother Teresa was a horrible person. Mother Teresa was a wonderful person. Which statement you believe is important. We should want to believe as many true things and as few false things as possible. But it’s also important why you believe something. Christianity puts a premium on truth.

A friend posted a link to Tim Challies’ The Myth of Mother Teresa on Facebook and a mini-debate erupted.

Just what Mother Teresa would have wanted.

An argument on Facebook? Say it isn’t so!

What surprised me were the reasons people didn’t like the article:

- The article was based on a suspicious source, notably the late Christopher Hitchens.

- The results of Mother Teresa’s work was positive not just to those she helped but to those who were inspired by her example to serve others. Therefore, we souldn’t smear her.

What should concern people, especially Christians, is whether or not the article was true. The objections on FB were like shooting at the flags atop a bastion rather than storming the gate.

Bad Sources (Objection #1)

Suspicious sources should always make us… suspicious. But suspicious doesn’t mean untrue. Christopher Hitchens was mistaken about a lot of things. He was philosophically weak as can be seen from his dialogues with Douglas Wilson and William Lane Craig. But boy could Hitch land some real zingers. Zingers can win an audience but not a debate.

Christians should avoid biased thinking that goes something like this:

- Christian always tell the truth.

- Non-christians always lie.

What gives a statement is truth value is whether or not it corresponds to reality not the source (except in the case of God).

It’s okay to attack a source but proving that the source was Hitler (to take an extreme example) doesn’t prove the argument that cites that source incorrect. For example, people have argued that Naziism was anti semitic. To prove their point they cite a speech by Hitler in which he rails against Jews. It would be silly to respond by saying, “You can’t cite Hitler because he was a really bad guy.”

Christopher Hitchens may have told hundreds of lies a day and still be a reliable source when it comes to Mother Teresa.

Incidentally, Hitchens was not the only source for Challies’ article.

[Tweet “Christians can use a source in good conscience if they’ve done their due diligence.”]

The Ends Justify the Means (Objection #2)

Some objected to the smearing of MT because of all the good she did. They might say, “Even if we grant that she wasn’t all that great she certainly inspired a lot of others to do good works.”

There are two problems with this objection:

- Whether or not MT did a lot of good is exactly what’s being questioned.

- The ends don’t justify the means.

Circular Reasoning: #1 is a problem because it’s an example of circular reasoning. Circular reasoning assumes what the argument is trying buy ativan 2.5 mg doses to prove. This type of argument isn’t very persuasive because it often sounds like, “Because I said so!” to the listener.

Demonstrably False: #2 is a problem because it’s demonstrably false. For example, suppose a person robbed a bank and gave the money to a children’s hospital. Donating stolen funds doesn’t justify the theft. For something to be moral it should have a good result in mind, but a good result (even if you can accomplish it) does not by itself make something moral.

Temporal vs Eternal Worth: Some say that those arguing that MT did some good may have an escape hatch. by distinguishing between deeds that have temporal worth vs eternal worth. I don’t accept that something can have temporal worth without having eternal worth. I’d rather stick with the idea of good in the eyes of man and good in the eyes of God.

None of these objections or my answers to them answer the question of whether or not MT was a good person, with good motives, who did good things.

The claim “MT did a lot of good” is an ontological claim.

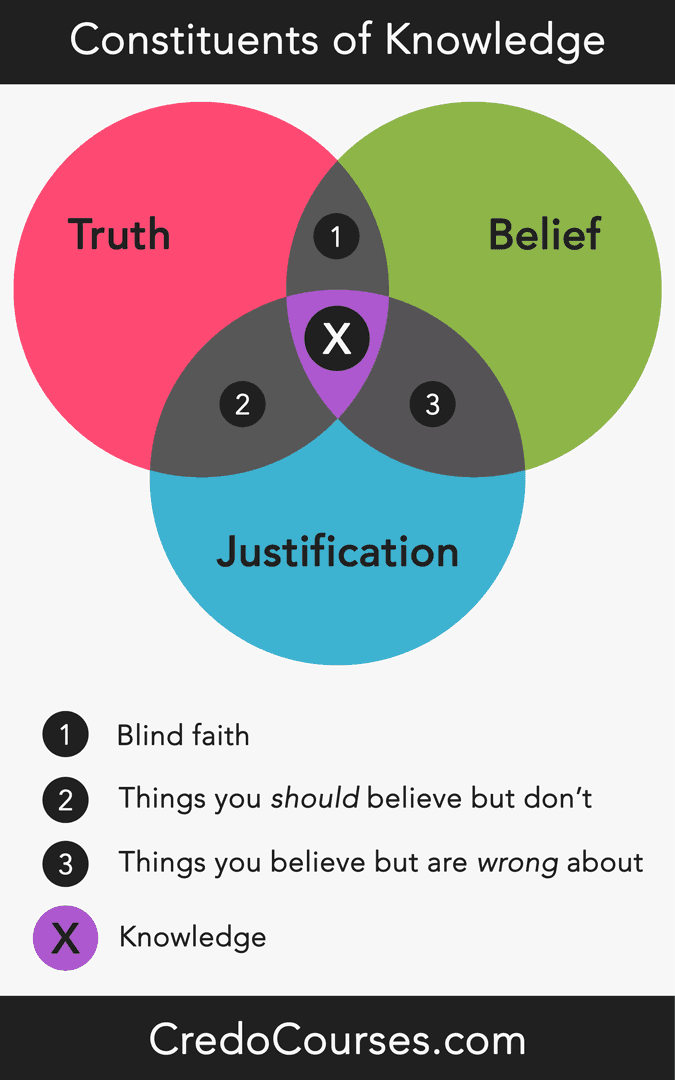

I want to encourage Christians to support their ontological claims with sound epistemology.

If you reject the stories about MT because of bad epistemology or accept them because of bad epistemology you both have room to improve.

Truth Seekers, Myth Busters, and Trolls

I wasn’t trying to convince my Facebook friends that Tim was right and MT was a horrible person. I’m not trying to convince anyone of that now.

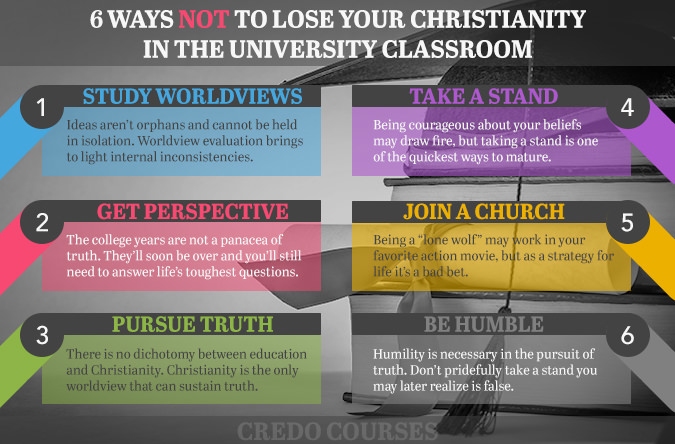

The goal is to help Christians focus on their commitment to truth.

Ben Shapiro in a speech at the University of Missouri made it very clear what he cared about:

I want to go through all of these specifics because I think it’s important for people to actually assess whether or not these things are true in the United States at current. Let me put one thing first, I don’t care about your feelings.[1]

Christians may choose to use different language to express the same idea. Truth trumps tone. A lie spoken sweetly is no better than one brutally expressed. Truth is objective. Tone is subjective.

Todd Friel talked about the number one sin in evangelical churches today:

[Tweet “Trolls stir things up. People don’t like trolls. Christians should be good trolls.”]

Trolls stir things up. People don’t like trolls. Christians should be good trolls. They should stir things up. Not just for the sake of it but because the things we need to talk about are out of bounds. Whenever you see a Christian leader’s life exposed those doing the exposing are often despised and attacked. There’s a right and wrong way to deal with sin. I’m not arguing against that. But let’s not vilify those exposing false doctrine, theology, or practice.

I couldn’t tell if I got through to the folks on Facebook. I hope I did.

Christians are followers of Jesus. Jesus called himself “the way, the truth, and the life.” That should matter to us.

You can see seven other reasons why Christians should care about truth and education here.

- Shapiro, Benjamin A. “Ben Shapiro Destroys the Concept of White Privilege.” YouTube. November 28, 2015. Accessed December 28, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rrxZRuL65wQ. ↩

- I have to give a shoutout to my friend Jon Winsley for his helpful feedback and critique.