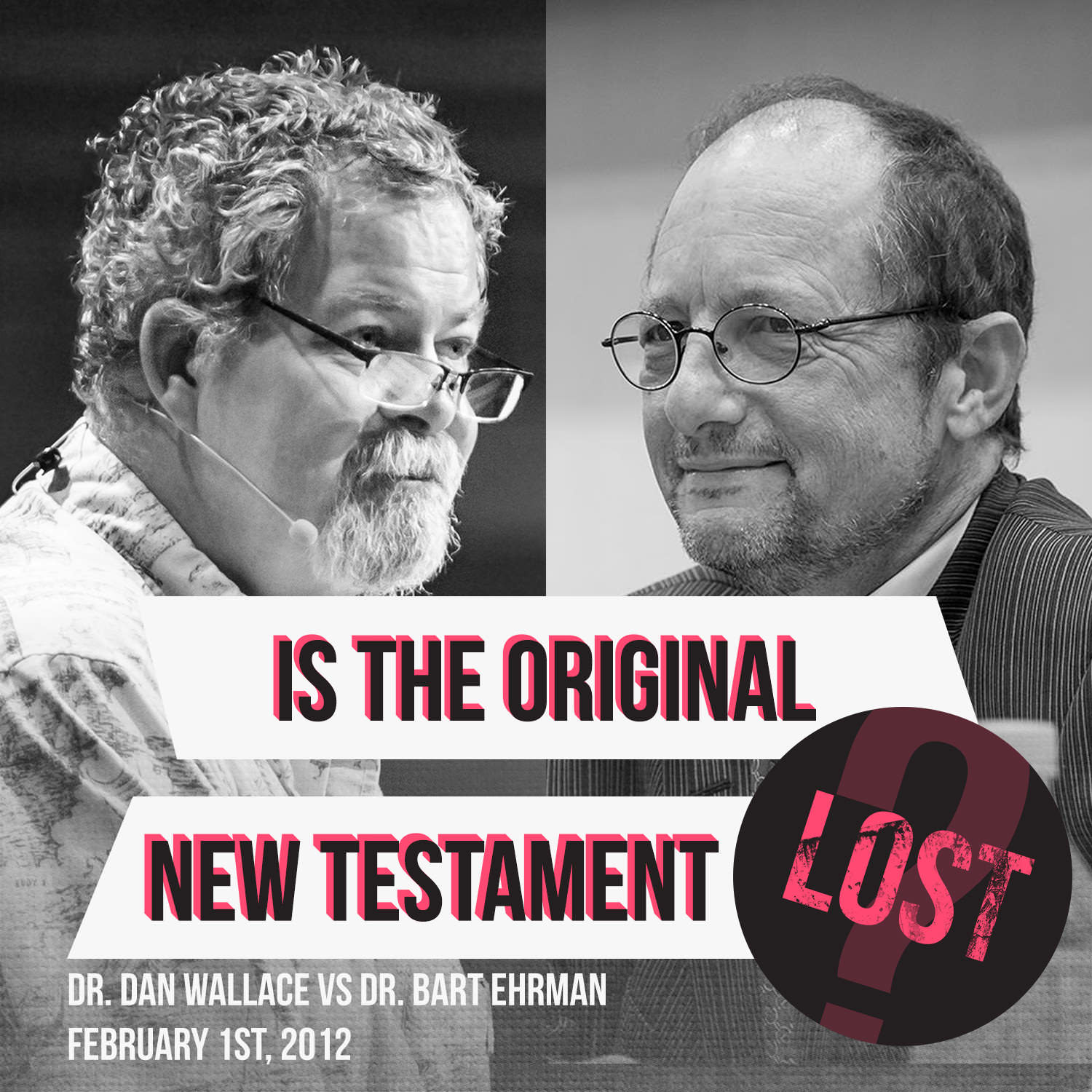

Is the Original New Testament Lost?

What: A Debate

Thesis/Resolution: Is the Original New Testament Lost?

Who: Dr. Bart Ehrman, Dr. Dan Wallace

Where: The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Memorial Hall Performing Arts Theater

When: February 1st, 2012

Dr. Ehrman’s Opening Argument

Well thank you very much. Thank you Miles for organizing this event and for flying in Dan Wallace to beat my rear side all over the stage. Appreciate that very much.

So, it seems like there are a lot of students here. Am I right? How many of you have had a class with me before? Ha ha! How many of you never want to take the class with me? Right. Okay. [audience laughter] How many of you in here, students or otherwise, would consider yourselves to be Bible believing Christians? Ha! Right. That would be all of you. [audience laughter] How many of you do want to see me get creamed? Right. [audience laughter]

Let me stress something at the outset. This debate is not a debate about the validity or the importance of the Bible. Nothing that I say will be directed against anybody’s belief. I will not be arguing a view that opposes the Bible in the least.

Quite the contrary. The position I will be staking out is the view held by a very wide range of Bible scholars many of whom are deeply committed Christians as well as a number of deeply committed Christians who are not Bible scholars.

The initial question seems to be missing from our overhead.

Projector?

[audience laughing]

Yes we’re sailing in Greece trying to find our togas.

So far I’m having fun. How about you?

Thank you very much.

[audience applauding]

And with that, let me conclude.

The topic of our discussion is, “Is the original New Testament lost?” There is a very simple and forthright answer to that question and I think Dan Wallace, in fact, will not disagree. The answer is, yes. We do not have the originals of the New Testament. Period.

Even down to its composition and the ingredients that are used. “Valium Diazepam” is a drug that is prescribed to help people cope with severe anxiety. In other cases – Valium or Diazepamis used to help with muscle spasms, inflammation, nerve disorders, and other https://www.honormyhealth.com/ordervaliumonline/. Diazepam is a generic medicine that is 90 % identical to that of branded Valium. This is not a drug that is prescribed for simple stress and typical anxiety most people that are on it have severe cases of anxiety or panic attack. The Drug has also been used to help treat delirium tremens or shakes associated with alcohol withdrawal.

In order to understand what I mean by that we have realize how books were made in the ancient world.

In the ancient world when the Bible was produced books could not be mass produced. This was before electronic publication, Kinkos, or the printing press. Books were written by hand and they were copied by hand. If you wanted a copy of a book somebody had to copy it for you or you had to copy it yourself.

You copied it one page, one sentence, one word at a time.

What happens when somebody sits down to try to copy a book by hand? Invariably what happens is they make mistakes. Either on purpose or accidentally.

Scribes who copied texts in the ancient world changed their texts.

Let me explain how it worked by giving an example from the New Testament, the Gospel of Mark.

We’re not sure who Mark was, when he lived, where he lived. Whoever he was the wrote a Gospel. If anybody wanted a copy of this Gospel of Mark they had to make a copy by hand and so they did so. But invariably they made a mistake, or two, or three, or twenty.

When someone came along who wanted a copy of that copy they copied the copy and they replicated the mistakes that the first copyist made. I have started to have problems with it recently, so I don’t understand what is better: to buy drugs or to go to the doctor because I was embarrassed. I bought Cialis pills and decided to try whether it really worked as well as I had read on the forums. I took https://www.chineseintelligence.com/order-tadalafil-online/, and felt the necessary effect. You feel much more confident when you take the drug. I decided to make sure on my own experience that this is true, I just had nothing to lose, because nothing helped.

And they made their own mistakes.

And then when a third person came along to copy the copy of the copy they replicated the mistakes of both of their predecessors and made mistakes of their own.

And it went on like this, week after week, month after month, year after year, decade after decade, century after century.

The only time mistakes got corrected in the process was when somebody was copying something and realized that there was a mistake and thought that his predecessor had made a mistake and so tried to correct the mistake.

The problem is there’s no telling whether a person who corrected the mistake corrected it correctly.

It’s possible that he corrected the mistake incorrectly. In which case you have three forms of the text, the original text, the text that was changed, and the incorrect correction of the change.

Things like that go on for a very long time.

We don’t have the original copy that Mark made. We don’t have the first copy. We don’t have copies of the copy. We don’t have copies of the copies of the copies of the copies of the copies of the copies. The earliest copy that we have of Mark dates from around the year 200. Probably about a valium easy order online hundred thirty years after the original. That’s the first copy that we have. A hundred and thirty years after the original.

We don’t have the originals of Mark, or of any other book of the New Testament.

The bigger question though is not whether we have the originals; the question is whether we can reconstruct the originals that have been lost.

Can we reconstruct them or not?

For many years I thought that the answer was yes. That’s going to be Dan’s answer.

But scholarship changed and it became widely thought among scholars that we cannot reconstruct the original and that it does not even make sense to talk about the originals.

I started to understand why and now I’m convinced. I can’t give the full argument here, but I can mention three major questions that all point in the same direction. These are 3 problems in dealing with what I’m calling the original text.

Problem one will be, what does it even mean to use the term, “original text”?

Problem two, where are the early manuscripts of the New Testament?

And problem three, why can’t scholars agree?

So these are the three problems that I’ll talk about in my 30 minutes with you.

What Does It Even Mean to Use the Term, “Original Text”?

What does it even mean to use the term, “original text”? I’m going to use one book of the New Testament as a particular example, 2nd Corinthians.

2nd Corinthians is one of the letters written by Paul to his congregation in the city of Corinth. One of the Pauline epistles.

It can illustrate well why scholars are reluctant these days to talk about the original text on theoretical grounds.

The Time Gap

To begin with we’re missing the original. Whatever Paul wrote we no longer have it. Our earliest copy of 2nd Corinthians is a manuscript called P46. It dates from around the year 200.

2nd Corinthians was probably written sometime in the 60’s and so we’re talking about a manuscript that was a hundred forty years after the original, is our first manuscript of it, and it’s not a complete manuscript. Our first complete manuscript of 2nd Corinthians does not come until about the year 350. In other words, nearly 300 years of copying, copying, copying, copying, with mistakes being made everywhere along the line, before we have the first complete copy.

So that’s obviously a problem, but it’s not the big problem I want to talk about.

Written, Dictated and Corrected

There are theoretical problems with even imagining what it might mean to call a text the original text of 2nd Corinthians for several reasons.

First, this first thing might seem a little picayune and sort of trite to you but in fact it’s actually kind of interesting. We have good evidence that Paul dictated his letters to scribes who wrote down what he said. In other words, he didn’t write himself, he dictated. We have solid evidence of this in the New Testament itself. We also have solid evidence from antiquity that when scribes took dictation they often made mistakes. They misheard a word, somebody in the room coughed and they didn’t hear it right, they weren’t paying attention, they wrote something down wrong.

Suppose Paul dictated what we’re calling 2nd Corinthians and the scribe wrote down wrong words. What is the original text? Is it the words that Paul spoke or the words that the scribe wrote down? We don’t have access to what Paul spoke just what was written down but what was written down might have had mistakes in it.

Moreover, suppose what happened was what happened frequently in the ancient world which is that the author looked at the written text once it had been written down and made corrections to it. Then what is the original text? Is the original text what the scribe originally wrote or is it what Paul corrected? If it’s what Paul corrected then we’re in the ironic situation that the later form of the text is being called the original text. And that could have happened a lot. But as I said, you might think that’s kind of a minor matter, and it’s not the biggest problem. It’s just an interesting problem.

The Problem of Splicing

There’s a bigger problem with respect to Paul writing 2nd Corinthians which is that Paul did not write 2nd Corinthians.

Paul did not write the letter of 2nd Corinthians as it has come to us today. Scholars have long recognized for over a century that 2nd Corinthians is made up of at least 2 different letters that have been spliced together. Chapters 10 through 13 do not come from the same letter as chapters 1 through 9. Not only that, there’s a large number of scholars, in both the United States and in Europe, who maintain that 2nd Corinthians, in fact, is made up of 5 separate letters that Paul wrote.

In other words Paul wrote 5 letters and they were put in circulation and were copied. And changed. Five letters. These were circulated and changed until somebody created our 2nd Corinthians by taking parts of these 5 letters and cutting them and pasting them together.

This is a standard view in scholarship. You will find this taught in every major research university in North America, what I’m telling you now. This is not some kind of crazy idea that a particularly liberal professor at Chapel Hill thinks. Although it is that. But it’s not just that. This is standard fare, virtually everybody who’s a critical scholar agrees with what I’ve just told you.

But what does that mean then? Somebody created the letter some years, maybe a couple decades, after Paul wrote, so that Paul didn’t create 2nd Corinthians Paul created up to 5 letters that had been in circulation probably changed that were then combined into 2nd Corinthians with a lot of the stuff cut out and other stuff put together.

Then this letter, this amalgam is put in circulation and it’s changed over time.

The Published Collection Theory of Günther Zuntz

And then something else happens that equally significant, even more significant.

It was argued over 50 years ago by one of the great scholars of the world of textual criticism, a man named Günther Zuntz, that around the year 100 some editor came along and collected the letters of Paul into one manuscript. That there were separate letters that were floating around, being transmitted here, there and the other… and somebody collected them into a collection and this collection was published.

This editor who collected the letters put the letters together and possibly put his own stamp on them. In other words, edited these letters to make them fit together into the collection. And then it was the collection that was put in circulation. Zuntz argued that all of our letters of Paul go back to that collection.

This is not a weird point of view by just one particular scholar. Günther Zuntz’ view has been supported by scholarship ever since. Most recently supported, for example, by a very important book written by Harry Gamble, who I am sorry to say teaches at the University of Virginia. But he’s a nice guy anyway and he’s very smart and he’s one of the most recent people to argue this; that the Pauline letters were not circulated just individually but around the year 100 they’re put into a collection and that all of our manuscripts of the letters of Paul go back to that collection.

Or there may have been even more than one collection. But the Pauline letters were not circulating individually they were circulated in collection and as they circulated in the collection of course they got changed as scribes changed the manuscript. And so this leads us to the very pressing problem, what is the original of 2nd Corinthians? It’s a great question and there’s not an easy answer.

There are a couple obvious options. You could say that 2nd Corinthians was the original letter that Paul wrote. Well apart from the problems of dictation you’ve got the problem that Paul didn’t write a letter. Paul wrote 5 letters, or 3, or 2. He wrote several letters and 2nd Corinthians was not one of them. Second Corinthians was a later amalgam made by a later editor of Paul.

So the original writing of Paul is not the original 2nd Corinthians, so maybe you could say that the copy that was later created by cutting and pasting is the original 2nd Corinthians. Well you could say that but Paul didn’t write that. He wrote the individual letters that were later cut and pasted together.

Moreover we don’t have access to this letter that was made by combining these various letters what we have access to is the collection. Because we don’t have manuscripts that go back to the letters that were circulating independently before the collection. All of the manuscripts that we have go back to the collection. We can’t get behind the collection. And so, what is the original? And who is to say?

We can’t reconstruct anything before the collection was made because we don’t have any manuscripts that go back to those individual letters before that event. But if we try to reconstruct the original form of the collection that’s not the original form of the text that Paul himself wrote. Moreover the one letter we’re interested in in the collection, 2nd Corinthians, was not one letter but 3, or 4, or 5.

This is a very confusing situation but it’s the historical realty which is one of the reasons – one of the reasons – why top scholars throughout the English speaking world have abandoned the idea that we can reconstruct some kind of original text. It’s impossible to know even what it means to speak of an original. And 2nd Corinthians is not the only problem.

The book of Acts in the New Testament, the fifth book of the New Testament, appears in two different forms in our manuscripts. Two major forms of the text. One form of the text of the book of Acts is 8.5% longer than the other. Many scholars think that whoever wrote Acts, call him Luke, published two editions of the work; a shorter one and a longer one that he later edited. If so, what is the original? The shorter or the longer?

The Gospel of John, scholars have long recognized that the epilogue found in John chapter 21 where Jesus has several resurrection appearances before his disciples was not originally part of the Gospel of John but was tacked on later. It wasn’t originally there. Again, this is just a common view among New Testament scholars throughout Europe and North America. But all of our manuscripts have it so what is the original text of John? Is it with 21 or without 21?

And what about the prologue of John? That very famous passage, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” This passage, the prologue of John, has numerous themes found nowhere else in the Gospel of John and the writing style is radically different from everywhere else in the Gospel of John so that many scholars [garbled] chapters 1 verses 1 through 18 were added to John after it had originally been published. Yet all the manuscripts have it so which is the original text?

The Gospel of Luke. Luke begins with the story of Jesus’ virgin birth in Bethlehem, chapters 1 and 2. But scholars have long recognized that chapter 3 looks like the original beginning of the book, that it didn’t originally have chapters 1 and 2. But the manuscripts all have chapters 1 and 2. So what is the original text? If it was originally published without chapters 1 and 2 shouldn’t we begin our Bibles with Luke chapter 3?

Or the Gospel of Mark. Mark’s Gospel ends with the women going to the tomb after Jesus has been raised from the dead, seeing a man there who tells them that they’re to go to Galilee, tell the disciples to go to Galilee, where Jesus will meet them. But the women flee from the tomb. They don’t say anything to anyone for they were afraid. Period. End of Gospel.

Many scholars think that the Gospel ends too abruptly. You can’t end a Gospel without the Jesus showing up to the disciples after the resurrection. And many scholars think that a page has been lost. If a page has been lost from the end of the Gospel what’s the original Gospel? If it’s the Gospel with the original page we don’t have any access to it. If you say it’s the Gospel without the original page than you’re saying a later form of the Gospel is the original Gospel and that hardly makes sense.

And so we have it.

A problem with the original. How do we know what the original is? Does it make sense even to talk about the original? This is the theoretical problem we have in even mentioning the original.

So that’s problem one. What does the “original text” even mean.

Where are the Early Manuscripts of the New Testament?

Problem two, where are the early Manuscripts of the New Testament?

The Number of Manuscripts

Let me say something about the surviving copies of the New Testament. Today we have some 5,500 copies of the New Testament. By last week the official count was 5,560 manuscripts that had been catalogued of the Greek New Testament. And the New Testament was originally written in Greek. That is far more than for any other book in the ancient world. Far more than any other. Way more than any book of Homer, or of Plato, or Aeschylus, or Sophocles, or Euripides, or pick your author. We have far, far more manuscripts of the New Testament than any other book in the ancient world by a long shot.

So, just take that as a given.

And the reason’s obvious. Because the people copying books in the Middle Ages were monks in monasteries. They’re the ones who gave us our surviving books. And which books were they interested in? Where they principally interested in Aeschylus or Plato or… not principally. They were principle interested in the Bible. So they copied the Bible. That’s why we have thousands of these manuscripts.

The Age of the Manuscripts

The problem is not the number of manuscripts or the fact that we have more than for any other author of antiquity. The problem is the ages of these manuscripts.

How many manuscripts of the New Testament do we have from the first Christian century? None.

From the decades after the books were written, how many do we have? The years afterwards, the decades… none! Zero.

How many do we have from the early second century, say manuscripts that clearly date up to around the year 150? We have one scrap.

This is it.

This may look big because it’s a big screen. This is the actual size. It’s the size of a credit card. It’s written on both front and back. It’s from John chapter 18. It has several verses on it. You can see this little scrap has parts of seven lines on it. It’s a very important manuscript because it’s the earliest one we have. It’s the early 2nd century. And it is the only manuscript we have from the early 2nd century. That’s it!

How many complete manuscripts do we have from the 2nd and 3rd centuries? We’re not just talking about decades now after these things were originally written and copied, and mistakes made and mistakes replicated, and then more mistakes made and more replicated. We’re not talking about years or decades we’re talking about centuries.

How many complete manuscripts do we have from the 2nd and 3rd centuries? None. Zero.

Well, if we have 5,500 manuscripts where are they from? When are they from? Well, 94% of our surviving manuscripts come from the 9th century and later. 94% come from the 9th century… which is great if you want to know what the Bible looked like when Christians were reading it in the year 890. But if you want to know how they were reading it in the year 70, you’ve got a problem. Because you don’t have manuscripts from that period.

If you wanted to make a stack of the Bibles that are available to scholars today in manuscript form the stack would go up the ceiling. If you want to make a stack of the manuscripts that were made within, say, 60 or 80 years of the production of these books, you wouldn’t be able to see the stack if we put it on the stage.

Cause there’s hardly anything.

The Number of Mistakes in the Manuscripts

Let me say a few more things about the surviving copies of the New Testament and point out some of the problems we have with the surviving manuscripts.

First, number of mistakes. I’ve told you that when scribes copy manuscripts they make mistakes. And maybe you’re thinking, “Yea well says you. Is there like evidence of this or is this just one of your other crazy opinions?” Well again, it is one of my crazy opinions but there turns out to be evidence.

We have 5,500 manuscripts of the New Testament. It is striking that when you compare these with one another in detail no two of them are exactly alike in their wording. They all differ. Well how do they… why do they differ? Because people are changing the text. Well, how many differences are there exactly? So, scholars have wondered about this for over 300 years. In the year 1707 there was a famous scholar named John Mill who was an Oxford scholar (not related to John Stuart Mill whom you may have heard of before). This is a different John Mill.

John Mill spent thirty [garbled] years of his life studying the manuscripts available to him. He had about a hundred Greek manuscripts that he could examine. And he had the quotations of the New Testament in the ancient translations of the New Testament into Coptic, and Syriac, and Latin and so forth and he had some quotations of the New Testament in the writings of the church fathers. And he had a bunch of evidence and he looked this evidence and in 1707 after 30 years of labor he published a book called the Novum Testamentum Graece the Greek New Testament.

In this book he gave a few lines of the text of the New Testament and then below it indicated places where the manuscripts he looked at differed from one another.

So this was an apparatus of readings. The apparatus showed were the manuscripts differed from one another. To the shock and dismay of many readers, John Mill’s Novum Testamentum Graece, in the apparatus, he indicated 30,000 places of difference among the manuscripts that he had examined. 30,000 places where the manuscripts differed from one another. And he was looking at a hundred manuscripts.

We have 5,500 manuscripts today. Well how many differences are there among these manuscripts exactly? No one knows. Because no one’s been able to count them all. Some scholars say 200,000 differences. Some say 300,000 differences. Probably more accurately 400,000 differences. It’s easiest to put it in comparative terms. There are more differences in our manuscripts than there are words in the New Testament. That’s a lot of differences. Well, those are the differences we have.

What about difference that were put into the manuscript before our surviving copies started appearing? Our New Testaments today, our Novum Testamentum Graece, are largely based on manuscripts produced in the 4th century. Sometimes manuscripts in the 3rd century are help… sometimes they’re extremely helpful, sometimes they’re relatively full. But for the most part, our Greek New Testaments agree with manuscripts found in the middle of the 4th century. Two manuscripts in particular.

These 4th century manuscripts differ significantly from the manuscripts of the 9th century. The 4th century manuscripts we rely on differ significantly from the ones from the 9th century. If they differ significantly from the 9th century manuscripts why should we think that they are very similar to the manuscripts of the 1st century? We simply can’t tell because we don’t have any 1st century manuscripts to compare them to. But there are several things that we can say.

Our earliest surviving manuscripts, the papyrus manuscripts that are very old, older than the 4th century, differ from one another more than the later manuscripts differ from one another. And the early manuscripts differ more from the later manuscripts than the later manuscripts differ from one another. This shows that the early transmission of the text was not carefully controlled.

Moreover, the scribes who produced these earliest manuscripts, as a rule, appear to be much worse than the later scribes. As a matter of fact, it is generally conceded by textual scholars throughout the world that the most radical changes to the text of the New Testament were made during the first 150 years of its transmission.

During the first hundred fifty years is when most of the changes were made, but those are the centuries for which we have no manuscripts. The later manuscripts that we do have were all based on those earlier ones that were lost that appear to have been quite different from one another.

What possible grounds could we have for assuming that the earliest manuscripts, whose copies we don’t have, produced highly accurate accounts? What evidence could we have? We don’t have evidence.

How important are all these mistakes? 400,000 mistakes. How important are they? Two things to say.

First, most of these mistakes, in fact, are not important at all. Let me stress this point as I think Dan will probably want to stress it as well, most of the mistakes we have in our manuscripts are completely insignificant, immaterial, and matter for nothing more then to show that scribes in the ancient world could spell no better than students can today.

And scribes didn’t have spell check.

I mean. I don’t know about Dallas Theological Seminary, but at UNC it’s a complete mystery. How do students turn in papers with misspelled words? The computer tells you it was misspelled! How smart do you have to be? It’s got a red line under it.

[audience laughter]

Anyway. Scribes didn’t have that luxury. Scribes didn’t even have dictionaries. Scribes often didn’t care how they spelled words. We know that scribes didn’t care how they spelled words cause sometimes you have a scribe writing the same word on 3 lines in 3 different ways. He just didn’t care.

And all 3 would count as a difference.

Lots of differences don’t matter. Sometimes scribes will leave out a word, they’ll leave out a line. Sometimes scribes would leave out a page. I mean that would matter but you can tell when it’s happened and so it’s not a big deal. Most things don’t matter. There are some changes though that matter.

Some of the differences in our manuscripts matter a lot. Not 400,000 of them. But a lot of them do as we’ll see in a minute.

Let me summarize what we have. We have lots and lots and lots and lots and lots and lots and lots of copies of the New Testament as Dan will no doubt stress. We have lots and lots and lots more copies of the New Testament than any other book in the ancient world without any other book even coming close. That’s absolutely true. That’s what we have.

What we don’t have are lots of early copies which are the copies that we want. And we don’t have lots of accurate copies. What we want are early and accurate copies and we don’t have them. So it’s not good enough to say we have lots of manuscripts if you can’t say that we have reliable manuscripts and early manuscripts.

Why Can’t Scholars Agree?

My first problem was… my timer… my second problem… my first problem, what does the “original text” even mean? Second problem, where are the early manuscripts? And my very quick final third point, “Why can’t scholars agree?”

If we can get back to the New Testament reliably, if we can reliably reconstruct the original Greek New Testament, why haven’t we? It’s not for want of effort. Scholars have massive disagreements on this, that, and the other thing up and down the line, year after year, decade after decade. Scholars can’t agree on what the original text is supposed to be.

Over the centuries these disagreement have been very important. They have involved such crucial doctrines as the doctrine of the Trinity—which relates to textual problems. The full divinity of Christ, effected by textual problems. The full humanity of Christ, effected by textual problems. The atoning sacrifice of his death, effected by textual problems. Favorite stories of Jesus’ life, effected by textual problems.

The proof of the pudding is in the tasting.

In the year 2005 there were two scholars who put together an edition of the Greek New Testament which they claimed was the original New Testament, the original Greek. Five years later in the year 2010, another scholar put together an edition of the Greek New Testament. It differed from the 2005 version in nearly 6,000 places.

After all the manuscript discoveries we’ve made, after all the technological developments, after all the methodological developments, after all the research we have two editions that differ in 6,000 places.

And that’s only counting the places that are mentioned in the apparatus. No one knows how many times they differ overall. At least the 2 editors don’t because I asked them yesterday.

Conclusion

Let me draw conclusions very quickly. I have addressed the question whether the original New Testament is lost. And the answer is absolutely, yes. It is lost. I’ve asked can we reconstruct the lost originals and here I have pointed to what I consider to be insurmountable problems.

The three questions I’ve asked are questions that Dan is going to need to answer for us.

It will not be good enough for him to say that we have lots and lots and lots of surviving manuscripts. Or that we have more manuscripts than for any other writing from the ancient world. Both things are true. But they do not address the problems. The problems are that we don’t even agree among ourselves what it means to talk about the original text. That even though we have many thousands of manuscripts from later periods we do not have any manuscripts from the early periods that we’re interested in. And that even though we may want to reconstruct the original text, however we define it, we have shown ourselves unable to do so, time after time after time.

According to the patients, the main benefits of Tramadol a reits high efficacy (even against severe pain) and fast action. Mean while, the main drawbacks of this drug arenumerous side effects, development of toleranceand, in some cases, addiction. Another group of reviews includes the feedback on the use of Tramadol in cancer pain treatment. These reviews are left not by the patients themselves, but by their relatives. The reason for this is that Tramadol is prescribed in advanced stages of cancer, whenthe treatment is aimed not at the patient’s recovery but at the provision of quick and pain less death. For additional information about the drug, visit https://tattooizm-studio.com/tramadol50mg/.

Thank you very much.

Dr. Wallace’s Opening Argument

Well good evening.

Bart and I have known each other for nearly 30 years.

He’s had a stellar career in New Testament studies especially in the field of textual criticism. I have the highest respect for his scholarship and more than that I’ve come to marvel at his quick wit, impressive rhetoric, and clear communication skills.

Not only that but he’s a really nice guy.

And I want to begin by saying that I’m deeply honored to share the stage with him tonight at the world famous Chapel Hill.

[audience applause]

Just wanted to see if you were paying attention.

The topic of this dialogue is “Is the original New Testament lost?”

If the question means are the original New Testament documents lost then yes, of course they are. Only quacks and charlatans, people who got their diplomas from a Cracker Jack box would argue otherwise. Bart and I don’t disagree on that point. But if that was the real topic it would make for a pretty boring dialogue and a good waste of your time and money.

But if the questions is, “Is the wording of the original New Testament lost?” as it certainly must, then Bart and I part ways on the answer.

I believe that we can be relatively certain that we can recover the wording of the original text. The operative words here are relatively, and confident. I believe that the wording of the originals is not lost but can be found somewhere in the existing manuscripts.

But the question of how certain we can be that we have found it really is a different matter which is in a sense a response to his last question, “Why do scholars disagree?”

I will also argue that although scribes changed the wording of the text for all sorts of reasons, they were unsuccessful in eradicating the wording of the original. It was both the orthodox scribes and the unorthodox who tampered with the text.

Two Extreme Attitudes to Avoid

But before we get into the topic directly I should mention two attitudes that rational people will avoid. Total despair or radical skepticism is the first. And absolute certainty is the second.

Absolute Certainty

On the one-side are King-James-Only advocates. They’re absolutely certain that the King James Bible, in every place, exactly represents the original text. I’ve actually heard them say, “If the King James Bible was good enough for Saint Paul it’s good enough for me.” [audience laughter] Usually with a West Virginia twang. [audience laughter increases] But this attitude is also one that many church-going Bible-believing Christians embrace without realizing that their modern translations change with each new edition.

[Tweet “If the King James Bible was good enough for Saint Paul it’s good enough for me.”]

Radical Skepticism

On the other side are a few radical scholars who are so skeptical that no piece of data, no hard fact is safe in their hands. It all turns to putty because all views are created equal. If everything is equally possible than no view is more probable than any other. Their mantra is, “We really don’t know what the New Testament original really said since we no longer possess the originals and since there could have been tremendous tampering with the text before our existing copies were produced.” Such skepticism over recovering the wording of the original text flies in the face of both reason and empirical evidence.

These two attitudes, absolute certainty and radical skepticism are like driving on the mountain roads in Greece. Drive too far to the left and you will have a head on collision with a tourist bus. Drive too far to the right and you will end up flying off the cliff where the guard rail should have been.

Rational people recognize that both extremes result in disaster. And that the only proper course is one of moderation.

Now, there’s four questions that I want to address tonight.

First of all, how many scribal changes are there?

What kinds of textual variants do we have?

What theological beliefs depend on textually suspect passages.

And finally the bottom line, is the original New Testament lost?

The Number of Variants

Well, I want to begin then with the number of the variants.

Let’s begin with a definition of a textual variant. It’s any place among the manuscripts in which there is variation in wording, including word order, omission or addition of words, even spelling differences. The most trivial changes count and even when all the manuscripts except one say the same thing that lone manuscript’s reading counts as a textual variant. And if a thousand manuscripts read “Jesus” in one place and another thousand read, instead, “Christ” that also counts as only one variant.

The best estimate is that there are between 300,000 and 400,000 textual variants among the manuscripts. I’m inclined towards the higher number. And yet there are only about 140,000 words in the New Testament. Now if this were the only piece of data we had it would discourage anyone from attempting to recover the wording of the originals.

[Tweet “The best estimate is that there are between 300,000 and 400,000 textual variants among the NT manuscripts.”]

But that’s not the whole story.

Why So Many Variants

The reason that we have a lot of variants is that we have a lot of manuscripts. It’s simple really. No classical Greek or Latin text has nearly as many variants because they do not have nearly as many manuscripts. If there were only one copy of the New Testament in existence it would have zero variants. Yet several ancient authors have only one copy of their writings still in existence and sometimes that lone copy is not produced for a millennium or more. But a lone, late manuscript would hardly give us confidence that that single manuscript duplicated the wording of the original in every respect.

This was recognized 300 years ago by the brilliant textual scholar Richard Bentley in his work, Remarks Upon A Discourse of Free-Thinking. Now Bentley was commenting on John Mill’s work of 1707 that Bart had mentioned where he discovered the 30,000 variants after collating a hundred New Testament manuscripts and Bentley sees this as a very positive thing for helping us to get back to the original.

If there had been but one manuscript of the Greek Testament, at the restoration of learning about two centuries ago; than we would have had no various readings at all. And would the text be in a better position then, than now that we have 30,000 variant readings? […] It’s good therefore, to have more anchors than one. And another manuscript to join the first would give more authority as well as security.

Bentley penned those comments in 1713 when only a hundred New Testament manuscripts had been examined.

Today, in Greek alone we have more than 5,600 manuscripts. Many of these are fragmentary especially the older ones. But the average Greek New Testament manuscript is over 450 pages long. All together there are more than 2,500,000 pages of text leaving hundreds of witnesses for every book of the New Testament. And Bentley was right. The Greek New Testament of his day has about 5,000 differences from the critically reconstructed Greek New Testament of today. As more and more manuscripts have come to light we are getting closer and closer to the wording of the original.

Because of the early Christians’ desire to spread the good news about Jesus’ death and resurrection, the New Testament was early on translated into a variety of languages: Latin, Coptic, Syriac, Georgian, Gothic, Ethiopic, Armenian, Old Church Slavonic and a host of others. There are about 10,000 Latin manuscripts of the New Testament alone. No one really knows the total number of these ancient translations, but the best estimates are that there are more than 5,000 plus the 10,000 in Latin. All together including Greek we have at least 20,000 manuscripts of the New Testament in various languages.

Now if someone where to destroy all those manuscripts, we would not be left without a witness. And that’s because leaders of the ancient church known as church fathers wrote commentaries on the New Testament and they did not have the gift of brevity.

To date, approximately 1,000,000 quotations of the New Testament by the father have been recorded. If all other sources for our knowledge of the text of the New Testament were destroyed the patristic quotations going back to the second century and in some cases even the first would be sufficient alone for the reconstruction of practically the entire New Testament wrote Bruce Metzger and Bart Ehrman.

Far more important than the number is the date of the manuscripts. How many manuscripts do we have in the first century after the completion of the New Testament? How many in the second, the third?

Although the numbers are significantly lower they’re still rather impressive. Last October when Bart and I have a debate in Dallas I said that we have today as many as a dozen manuscripts from the second century, all fragmentary, 64 from the third and 48 from the fourth. That’s a total of a hundred and twenty-four manuscripts within 300 years of the composition of the New Testament.

Most of these are fragmentary but collectively the whole New Testament is found in these manuscripts and several books are found in them multiple times. That’s what I said last October. But those numbers now need to be revised significantly in light of some recent findings and I’ll come back to these at the end of the lecture.

How does the average classical author stack up? If we’re comparing the same period of time, 300 years after the composition of the book, the average classical author has no literary remains. Not a single manuscript. None! Zero! But if we compare all the manuscripts of a particular classical author, regardless of when they were written the total would still average less than twenty. And usually less than a dozen and they would all be coming much more than three centuries later.

Stack them up and they’re about four feet high. Now how high would the stack of New Testament manuscripts be?

Well, let’s take a look.

I think that’s probably not high enough. Bart, I think said it went to the ceiling of the auditorium. It certainly think it would go that high I believe. It’s getting closer. That’s better. That’s even better. And that’s as much as I could do in Powerpoint.

[audience laughter]

There should be eight times as many New Testament manuscripts as you see here. And you put them in one stack and they’re over a mile high.

[Tweet “If you could stack them all up the manuscripts of the New Testament would be one mile high.”]

Now perhaps this seems a bit abstract. Let’s use money as an analogy. Let’s say the average Duke graduate represents the average classical author. And he earns $20,000 a year. Now, it’s a shame that that’s below the poverty level. [audience laughter] But, he made a choice to go to Duke and he has to live with it. Now if the average Chapel Hill graduate represents the New Testament she is earning $20,000,000 a year. [audience applause]

The skeptic repeatedly note that the vast majority of New Testament manuscripts come from at least 800 years after the completion of the New Testament. The implication they draw from this is that none of these manuscripts are trustworthy and that the New Testament is in no better shape than the other ancient literature.

But what they don’t tell you is that these later manuscripts add only 2% of material to the text. If we could envision the New Testament as a snowball rolling down a hill picking up alien elements through the centuries it is remarkable that it only picks up 2% more material over fourteen centuries.

Imagine a stock broker advising you to invest in a stock that grows only 2% every millennium and a half. Probably got his degree at Duke. [audience laughter]

What skeptics don’t tell you is how this compares to other ancient writers. For many important authors we only have partial works. Livy and Tacitus were two of the most important Roman historians of the first century.

We base most of our understanding of Rome on these two authors. Livy wrote 142 volumes on the history of Rome. Only 25% of them survive today. Only a third of Tacitus’ writings are still with us.

What we have of Pliny the Elders’ writings are 200 copies which is really significant. But we’re waiting 700 years for the first one. Plutarch’s Lives are found in manuscripts no earlier than 800 years after he wrote. Josephus’ Antiquities of the Jews, a really significant work and vital for us to understand Judaism of the first century, is found in more than 20 copies, none earlier than the ninth century C.E.

The earliest copies of Polybius the historian produced 1,200 years after he wrote. There are massive gaps in Pausanias’ Description of Greece, all of them coming more than 1,400 years later. Herodotus’ Histories has 26 copies, the earliest coming half a millennium after he wrote. That’s the earliest copy. We’re waiting 1,500 years for the first substantial copy. And we’re waiting eighteen centuries for any substantial copies of Xenophon’s Hellenica.

Now these are not obscure authors. They are some of the most important historians and biographers of the Greco-Roman world. Even for some of the better preserved writings there are gaps galore. One scholar complained that the surviving copies of some of these writings are filled with gaps, corrupt, dislocated, and interpolated. He then proceeds to lay out procedures, principles to fill in the gaps with nothing but his own reason because he can’t find the original wording in any manuscript.

Another scholar notes that for manuscripts of his author the chief blemishes are gaps in the text where the manuscripts tradition fails us entirely. The task of filling the gaps without manuscript testimony is absolutely necessary for most of Greco-Roman literature. And almost entirely unknown for the New Testament.

Now let me repeat that, the task of filling the gaps without manuscript testimony is almost entirely necessary, it’s absolutely necessary for most of Greco-Roman literature. And almost entirely unknown for the New Testament.

The very fact that we don’t have these gaps for the New Testament tells us that the manuscripts present a coherent picture. And if it’s coherent even among our earlier manuscripts it means that the text was stable even from the earliest times. That it didn’t radically change from one generation to the next. Did it change? Yes. But radically? I would disagree with that.

Skeptics also don’t tell you how many New Testament manuscripts we have in those earlier centuries. I’ve already mentioned the date or the data for the first three centuries. Here are the statistics through 900 C.E. We have at least three times more New Testament manuscripts today that were written within the first 200 years of the composition of the New Testament than the average Greco-Roman author has in 2,000 years. Three times as many within the first 200 years than the average Greco-Roman author has in 2,000 years.

Although only 10% of the Greek New Testament manuscripts were copied before the year 900, that’s still more than five hundred manuscripts. To argue that we don’t have very many New Testament manuscripts from the early centuries is only true in relation to later New Testament manuscripts. Not to anything else in the ancient world. J.K. Elliot, a meticulous New Testament textual critic, correctly notes, “We have many manuscripts and many manuscripts of an early date.”

Bart is right however that New Testament scholars have a serious problem on their hands. But it’s not the problem that plagues Greco-Roman scholars. New Testament scholars are confronted with an embarrassment of riches. If we have doubts about what the original New Testament said those doubt would have to be multiplied at least a thousand fold for the average classical author.

Now think about that. Are the skeptics really going to say that they have no idea what Plato, or Demosthenes, or Suetonius, wrote? Those of you who are history majors of ancient Greece and Rome, you might as well give up because we have no idea what they said. If these skeptic applied their skepticism of the New Testament text to the rest of Greco-Roman literature then we might as well kiss goodbye all our ancient history books. Because we would know next to nothing about the Caesars, Alexander the Great, Cicero, Plato, the glory that was Rome or millions of other facts that are preserved for us only in our manuscript copies of these authors.

Our modern democracy, medical ethics, mathematics, would all be eradicated. And most importantly Russell Crowe could never have played the lead role in Gladiator. [audience laughter] This kind of skepticism would thrust us right back into the dark ages where ignorance was anything but bliss.

Put simply the New Testament is far and away the best attested work of the ancient world. And precisely because we have hundreds of thousands of variants and hundreds of early manuscripts, we’re in an excellent position for recovering the wording of the original.

What Kinds of Variants Are There in These Manuscripts?

What kinds of variants are there in these manuscripts?

More than 99% make no difference at all. For example, the most common variant involves spelling. And this is a very common and is far and away… oh sorry… I was at Duke earlier today. [audience laughter]

[Tweet “More than 99% of the textual variants make no difference at all.”]

The most common spelling variant involved a moveable nu. You know when you put “n” on a word in English and the next word starts with a vowel, “an apple”, “a book” that kind of thing. Greek does the same thing. But not all the scribes put that nu on there. And so some of them said “a book, a apple”. But it means the same thing.

The smallest group of variants are those that are both meaningful and viable. What I mean by meaningful is that they change the meaning of the text to some degree. And viable means that they have a good chance of representing the original wording. Less than 1% off all textual variants fit this group as Bart and I would both agree.

For example, I’ll just give a couple of illustrations. Mark chapter 9 verse 29: Jesus’ disciples went out to cast out some demons and they were unsuccessful. And Jesus said, “This kind can come out only by prayer.” Some manuscripts—most later manuscripts—have “…and fasting.” So were those demons the kind that needed to be cast out by prayer and fasting, or would prayer do it alone? It’s an important variant, and you can tell just by looking at me that I go with the shorter reading. [audience laughter]

That’s why I’m hiding behind the podium so you really can’t look at me.

Revelation chapter 13 verse 18: “Let the one who has insight calculate the beast’s number for it is the number of a man and his number is six-six-six.” Well everyone knows that the number of the beast, the number of the antichrist is six-six-six. But a hundred and seventy year ago a scholar deciphered an early manuscript that says the number of the best was six-one-six. And that manuscript has proved to be one of the most valuable texts of Revelation. And just fifteen years ago another manuscript with six-one-six was discovered. And it happens to be the oldest manuscript of Revelation chapter 13. Now most scholars think that six-six-six is the number of the beast and six-one-six is the neighbor of the beast. You know he lives just a few doors down. But it’s not a settled matter. And if six-one-six proves to the better reading it will send seven tons of popular Christian literature to the flames.

Although the quantity of textual variants among the New Testament manuscripts numbers in the hundreds of thousands, those that change the meaning pale in comparison. Less than 1% of the differences are both meaningful and viable.

Now there’s still hundreds of texts that are in dispute. I don’t want to give the impression that textual criticism is merely a mopping up job nowadays, that all but a handful of problems have been resolved. That’s not the case. There are hundreds of passages whose interpretation depends to some degree on which reading is followed. And this fact leads us to our third question.

What Theological Beliefs Depend on Textually Suspect Passages?

In the appendix to Bart Ehrman’s Misquoting Jesus there’s a Q and A section.

The most telling question asked of Bart is this, “Why do you believe these core tenets of Christian orthodoxy to be in jeopardy based on the scribal errors you discovered in Biblical manuscripts?” Bart’s answer might surprise you, “Essential Christians beliefs are not affected by textual variants in the manuscript tradition of the New Testament.” I agree with him. So that question is dealt with pretty quickly I think.

The Bottom Line, Is the Original New Testament Lost?

Finally, the bottom line, in the original New Testament lost? [audience laughter] I offer five arguments that we can be relatively certain that we have the wording of the originals today somewhere among the manuscripts.

Chaos Not Conspiracy

First, Bart speaks of the first to hundred years as uncontrolled, giving the impression that all manuscripts of this era are riddled with mistakes both unintentional and intentional. The scribes, it seems, were undisciplined and wild, freely adding or subtracting words whenever they wanted to.

But if that is the case then scholars are in an excellent position for finding the original. Because there’s no conspiracy only chaos. Early copies were made in Alexandria, Rome, Antioch, Jerusalem. Then copies were made of those copies. And copies were made of those copies. We may not have the earliest copies, but we do have the copies of the copies of the copies. The very fact that they differ from one another shows that there was no conspiracy to produce just one kind of text.

We have Greek manuscripts, early translations and comments on the New Testament by church fathers that span the ancient Mediterranean world as well. The fact that they disagree often, as much as 10% of the time, means that there was no conspiracy and that most likely the original wording can be found in them somewhere. And when they agree we have the highest certainty that they represent the wording of the original text.

But what happens when these witnesses disagree? How can we determine which of them are better than others? Well the standard introduction to New Testament textual criticism by Bruce Metzger, the man who Bart describes as the best textual critic of the twentieth century, puts things in perspective.

It would be a mistake to think that the uncontrolled copying practices that led to the formation of the western textual tradition were followed everywhere the texts were reproduced in the Roman Empire. In particular there’s solid evidence that in at least one major sea of early Christendom, the city of Alexandrea, there was conscious and conscientious control exercised in the copying of the books of the New Testament. Textual witnesses connected to Alexandria attest to high quality of textual transmission from the earliest times. It was there that a very ancient line of text was copied and preserved.

Now we can illustrate this pure Alexandrian stream with three manuscripts that Bart and I would both agree are there of the best manuscripts of the New Testament and he’s already talked about two of them.

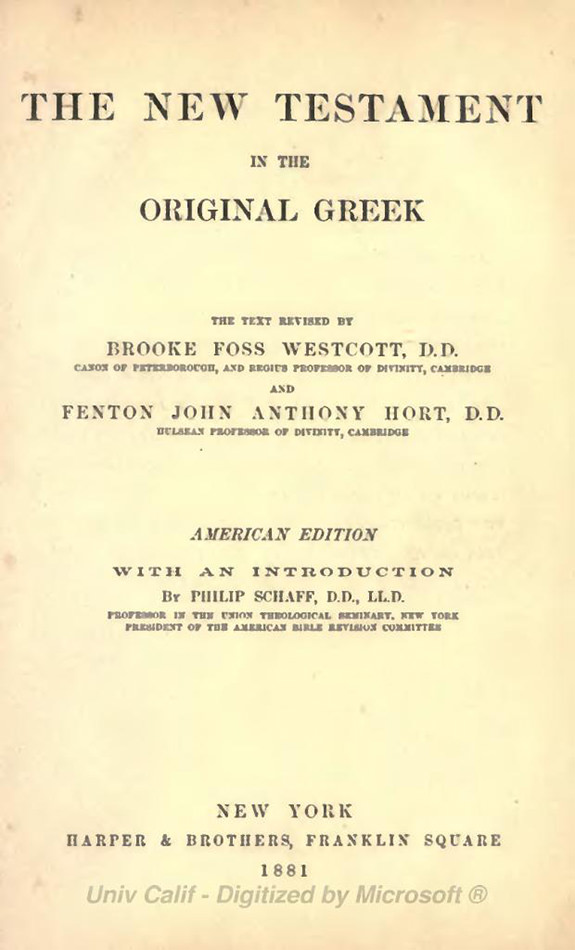

Two of these, Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus, are both from the fourth century. Here’s a picture of Codex Sinaticus to begin with. They were produced by professional scribes. There are thousands of differences between them. The vast majority of these of no consequence and yet together these two manuscripts attest to a very ancient, very pure form of text. The fact that there are so many differences between them shows that neither one was copied from the other and their remarkable similarities between them shows that they share a common ancestor but one that is several generations older than these two manuscripts. It must have been produced in the second century and most likely early in the second century. That’s the conclusion that two British scholars came to a hundred and thirty years ago before any of the early papyri were discovered.

And remarkably their judgement has been vindicated by the discovery, sixty years ago, of a very important manuscript, P75. This manuscript is closer to Vaticanus than it is to any other manuscript. P75 is a hundred to a hundred and fifty years older than Vaticanus and yet it is not its ancestor. Instead Vaticanus copied form an earlier common ancestor that both Vaticanus and P75 were related to. the combination of both of these manuscripts goes back most likely to early in the second century. And in combination with Sinaiticus this is a strong argument for the authenticity of the words in question.

But is P75 an anomaly? Are there any other manuscripts that are like it, that are both early and accurate? Yes. At least 17 of them. And they include portions of 14 New Testament books with nearly 500 verses found among them. Although many of our early papyri were done sloppily not all of them were. These 17 papyri confirm that Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus are excellent manuscripts who’s ancestry reaches back to the earliest times. Even though these two manuscripts are from the fourth century their wording is that of a text that is hundreds of years earlier.

Now, P75 is valuable in another way. The scribe who produced it was not a professional. He wasn’t trained in copying literary documents. His writing was legible but it looks pretty much like chicken scratches. But he was careful. He wrote one letter at a time. And the mistakes that he made are easily detectible.

In fact, almost all of the oldest manuscripts were made by scribes who were not professionally trained. But the kinds of alterations they made are almost always unintentional.

It would be like a scribe who copies out the preamble to the Constitution by writing, “We the people of the United States in order to form a more perfect onion.” Mistakes of this sort, as every textual critic knows, are the easiest to detect and the easiest to correct. It’s a simplistic and misleading argument to claim that since the earliest scribes make the most mistakes that these mistakes hide the wording of the original. It doesn’t take much of an imagination to change “onion” back to “union.”

The Original Is In the Manuscripts Tradition

And second, the standard Greek New Testament in use today is known as the Nestle/Aland text. It not only produces what the editors believe is the wording of the original New Testament but it also list tens of thousands of variants.

Here’s a picture of the text.

The editors list a hundred and sixteen places where scholars have thought that none of the Greek manuscripts have the original wording. Of those 116 places the editors accept only one: the addition of a single letter to the end of a word in Acts 16:12. Yet the two senior editors, Kurt Aland and Bruce Metzger, felt that even in that one place the original wording was not lost but was to be found in the manuscripts.

What Aland and Metzger were arguing is that when it comes to the wording of the New Testament it can be found either above the line or below the line in the Nestle/Aland text.

In other words, the original text is found in A, B, or C, but never any of the above, I mean none of the above, sorry.

The Papyri Confirm Later Manuscripts Finds

Third, let’s consider the papyri in another way. In the last one hundred and thirty-five years, one hundred and thirty-four New Testament papyri have been discovered. Some of them have been sensational discoveries. And they are, collectively, our earliest manuscripts of the New Testament. Some of them have very interesting wording in several places. Bart has argued that the earlier we go the worse mistakes the scribes make. The question I have is, how does he know that? What criteria does he use to determine that they made mistakes? Either such errors are patently obvious, like “onion” for “union”, or he is judging these early papyri by later manuscripts that have an excellent pedigree. Later manuscripts who’s wording reaches back to the time before our earliest papyri.

Significantly, not a single new variant found in the papyri has altered what scholars believe the original New Testament said. Not one. The papyri do not point to any variant that scholars have claimed, “Ah ha! We didn’t have that wording before and it must be original.” No the original wording was already found in the manuscripts that they knew about a hundred and thirty-five years ago. So what would happen if we found manuscripts even earlier than our earliest papyri? They will no doubt confirm the wording that we already consider to be original. If all the New Testament papyri that have been discovered have not been able to introduce a single original reading, why should we think that more discoveries would be any different?

An Early Copy of Mark in Matthew and Luke

Fourth, Bart has used the Gospel of Mark to illustrate his skepticism about the original wording. He pointed this out in our previous debate that our earliest manuscript is from the third century. And he said that again tonight. About a hundred and thirty years after Mark wrote his Gospel. Do we really have no idea what Mark’s Gospel originally said? Most scholars believe that Matthew and Luke borrowed heavily from Mark’s Gospel to write their own. In fact, 90% of Mark is found in Matthew. So we actually do have a first century copy of Mark, it’s the one that Matthew used. However, Matthew not only copied Mark he also changed it. Matthew removed Mark’s redundancies, smoothed out his awkward phrases, cleaned up his grammar and portrayed Jesus in a different light. But did Matthew have a perfect copy of Mark’s gospel to work from? Neither Bart nor I think he did.

One of my graduate students is writing his thesis on what this copy of Mark must have looked like. And remarkably he has found only two kinds of changes in just a handful of verses. The use of a word that means “and” in the place of a word that means “and” or “but.” And what’s called a “historical present” for a simple past tense verb. That’s it.

Yes it’s true that the copy of Mark that Matthew used is not identical with the original Mark. But the differences are so trivial that they can’t even be translated.

A First Century Fragment of Mark

Fifth and finally, to take Mark’s Gospel as an illustration again, even if we had no rock solid evidence of what Mark’s Gospel looked like in the first century we have overwhelming evidence that it is hardly different from what scholars have constructed from the available evidence.

Of course to demand a first century copy of Mark goes far beyond what is demanded for any other ancient literature. However, in the last few months several very early fragments of the New Testament have been discovered. These will be published by an international scholarly publishing house in a book one year from now.

By way of background, prior to this book, I mentioned that we knew of as many as a dozen second century manuscripts from the New Testament that were in the second century. Once the book is published the numbers will changes dramatically. As many as 18 New Testament manuscripts from the second century. Among the finds was also a fragment of Luke that is from the early second century; it thus rivals P52, that fragment that Bart showed you, the manuscript traditionally considered to be the oldest New Testament manuscript know to exist. And yet, this new Luke fragment is not the oldest New Testament manuscript. The oldest manuscript of the New Testament is now a fragment from Mark’s Gospel that is from the first century. How accurate is the dating? Well my source is a papyrologist who worked on this manuscript a man who’s reputation is unimpeachable. Many consider him to be the best papyrologist on the planet. His reputation is on the line with this dating and he knows it. But he is certain that this manuscripts was from the first century.

This papyrus fragment, just like the other new discoveries that we are preparing for publication strongly confirms what most scholars have already said is the original text.

Well in conclusion, is the original New Testament lost or is it found somewhere among the manuscripts? The evidence I have presented indicates that we have it in the manuscripts today. To be uber skeptical about this in the face of the mountain of evidence is to take a leap of faith where the guard rail should have been.

Thank you.

Dr. Ehrman’s First Rebuttal

Okay, thank you very much and thank you Dan for a very lively and interesting presentation.

It’s always enjoyable to have a dialogue with somebody who’s completely competent in the field.

I want to deal with several things in the short time that I’ve got.

First of all, I believe that when Dan kept saying “radical skeptic” I think he was referring to me. [audience laughter] I’m not completely sure about it but I think that’s what he had in mind. The term radical refers to… a radical view is a view that is so extreme that very few people hold it.

The views I laid out for you are not radical in that sense at all. In fact, the are widely held among scholars in this field. Arguably the most erudite scholar in North American in recent decades is the lately deceased William Peterson whose book Collected Essays came out two weeks ago, who argues in essay after essay that it does not make sense for us any longer to talk about the original text.

The senior person in the field of New Testament textual criticism in North America is named Eldon Epp. He teaches the text criticism seminar at Harvard University. He also has written essays arguing that it no longer makes sense to talk about the original text. The chair of the New Testament Textual Criticism section of the national Society of Biblical literature meeting is AnneMarie Luijendijk who is a professor of religion at Princeton University. She also does not think that it makes sense to talk about the original text. Her predecessor was Kim Haines-Eitzen who’s chair of the Department of Religion at Cornell University. She also does not think that we can talk about getting back to the original text. The leading scholar in the field in the English speaking world is David Parker who teaches at the University of Birmingham in England. He’s written an entire book arguing that you cannot get back to the original text and it doesn’t make sense to talk about the original text. These are not extreme views. These are the views of the leading scholars in the English speaking world.

What about Dan’s comments? He made several points that were, in fact, were points that I stressed, he stressed them a little bit more. He wanted to stress that we have lots and lots of New Testament manuscripts that you could stack them up a mile high. That’s absolutely right. He also insisted that we have more texts than we have for the classical authors. That’s absolutely right. I agree with both points. But they are notreally the key point.

Most of these manuscripts date from after the ninth century and they simply don’t help us if we want to know what the text was like 800 years earlier. And the irony is that Dan agrees. Dan has written numerous articles arguing that these late manuscripts are not accurate representations of the original text as he calls it. If we want to know the original text we need early manuscripts.

I don’t know where Dan is getting the figure of twelve manuscripts from the second century. I have in my hand the official listing. Put out by the Institute for New Testament Textual Research in Münster Germany. I checked it again last night. They date only four manuscripts defiantly going back to the second century. Four, these four, make up forty-two verses altogether. Forty-two verses out of the nearly 8,000 in the New Testament are what is represented in these second century manuscripts.

Dan has wanted to argue on several occasions that the fact that we have so many variants is a good thing not a bad thing. I don’t buy it. If we wanted to have a copy of the Declaration of Independence and what we had instead were 5,000 copies and these 5,000 copies of the Declaration of Independence differed from one another in 400,000 ways would you seriously think that was better than having 5,000 copies that didn’t disagree at all?

And it’s not necessary for hand written texts to have this many errors. If you know anything about Jewish copying practices through the middle ages, how Jews copied the Hebrew Bible as opposed to Christians copying the New Testament, Jews made sure there were no mistakes. And there were not variant readings. We don’t need these variant readings. We could do with out them. We’re not happy we have them because we have to weed through them.

Dan has argued that in Alexandria, all east, we had an accurate text. That’s true for when we actually had a text that came to Alexandria. My time is virtually up I’m going to leave with three questions for Dan.

First I want him to answer the question that I raised throughout my talk, “What does he mean by the original text?” For example, of 2nd Corinthians.

Second, some of the worst scribes on record were the earliest scribes. Everybody agrees on this. How good then were the scribes copying the text before the worst scribes? That is, what evidence do you have that the earliest scribes were competent at all. It won’t do for you to say that we have a copy of Mark in Matthew and Luke precisely because Matthew and Luke differ in numerous places when they’re citing Mark. I too, as it turns out, have a doctoral student doing a dissertation on this and he’s finding much more than trivia. They in fact were widely different.

My third question, how do we know that our earliest surviving manuscripts were based on highly accurate copies instead of truly awful ones that were full of accidental and intentional changes? What is the evidence?

Thank you very much.

Dr. Wallace’s First Rebuttal

Well I’m at a bit of a disadvantage because Bart got to present first and then got to ask questions of me and now it looks like I am supposed to answer his questions, and I’ll do that. But I’ll also ask him some as well.

What do I mean by the “original texts”?

I mean the text as it left the hand of the author when it was dispatched to his readers. 2nd Corinthians is a particularly difficult problem because it is true that many scholars, probably most scholars, believe that chapters 10 through 13 were added later but were also written by Paul. And that it was seemed together. But by no means do all scholars hold to that. But either way it is a difficult problem and I fully admit that to Bart.

But I don’t think 2nd Corinthians is representative of most of the New Testament books. It’s an exceptional book in that respect. The original text then is the text as it left the hands of the author.

Now, Bart mentioned that sometimes the original scribe who is copying it down for the author may well have made mistakes. And I would agree with that too. I think that the author would have corrected those places because Paul notes, for example, that he signs off on his letters and if he’s signing off on them just like a business man who’s signing off for his administrative assistant who’s typed up a letter, he’s signing that document to say this really is authoritative, it really is from me.

Bart mentioned also Mark 16 as an illustration along these lines, that we don’t have the original text of the end of Mark, Mark’s Gospel anymore. That may be true. However, it’s by no means the only opinion out there and I would say that it’s not even the majority opinion. He suggested that perhaps the last leaf of Mark’s Gospel fell off. That would be true if Mark’s Gospel were originally—or could be true if Mark’s Gospel were originally written as a codex. That’s our modern book that’s bound on one side with pages.

Most of you have not seen a codex because you only know the scroll on your computer screen. That’s older technology. But if Mark’s Gospel was written on a scroll as it almost surely was, than that last leaf would be the most protected. It’s like turning back your scrolls into the Blockbuster Video. You have to rewind the darn thing. That’s before everybody’s age here isn’t it? It goes back to VCR times. But Mark 16 would’ve been written on a scroll and consequently the last leaf, most likely, would not have been lost. But I think Mark intended to end it at 16:8. Nevertheless, that’s a minor point.

Bart also wants to know where the early manuscripts are and I would say that they are still being discovered and Myles I think you said that we’ve discovered 7 manuscript, it’s really 70 that we’ve discovered in the last ten years covering over 18,000 pages of text.

Bart also asked why can’t scholars agree. And he said there’s two texts that came out in 2005 that both presented the text as original, the original New Testament, the disagree in 6,000 places. Well, I think that’s overstated. I think that’s terribly overstated. The vast majority of New Testament textual critics are going to agree on the vast majority of textual problems.

Bart mentioned that when he, in one place, that if he and Dr. Metzger were to sit down and discuss what variants they thought were original, which ones were not, he said there’d be probably no greater difference than maybe a couple dozen places. So most scholars are going to agree with the text that we have today except in, at most, a few hundred places. Not a few thousand places. It’s the kind of a group that follows those ninth century and later manuscripts where they see as many as 6,000 differences from the earlier ones.

Well that’s how I would respond to some of these questions. But I have a few of my own as well.

First of all, I want to know if Bart can offer a convincing scenario in which the wording of the original text disappeared without a trace. Kurt Aland, Germanys best textual critic in the second half of the twentieth century at the University of Münster which is the epicenter for all New Testament text critical studies, whose institute poured thousands of hours looking over manuscripts claimed that no reading had ever made it into the manuscripts that had disappeared.

Bart is claiming that not only did several spurious reading have disappeared but so has the original wording. The very fact that we have a rather large amount of variant readings in the existing manuscripts is evidence that no one group was able to conform all the manuscripts to their own standard. That no one group was able to suppress the original wording.

And I have a second question, if Bart is this skeptical about the New Testament text, how skeptical would he be about the rest of the ancient Greco-Roman literature? I want to know if he thinks that we have no clue what these other authors said.

And just for the record, no I did not think of you when I wrote those notes about radical skeptic. But if you fit that’s okay.

Dr. Ehrman’s Second Rebuttal

Well I don’t know if any of you all have done these debates but let me tell you these rebuttals are not fun.

The one problem is, the five minutes when you’re giving one of these things seems like it lasts for a totality of about 20 seconds. Dan thinks that the original text is the text as it left the hand of the author. So what is the original text of 2nd Corinthians? What is the original text of John? Did it have chapter 21 or not, even though all the manuscripts have it? Did it have the prologue or not? What about the two versions of Acts, one eight-and-a-half times longer than the other? Which is the original version? Did Luke originally have chapters one and two? It’s in all the manuscripts.

Dan wants to point out that textual critics basically all agree on most of the text that they look at. The deal is this, all of these scholars who agree with me that it doesn’t make sense to talk about the original text don’t give up and go home. What they do is, they try to decide what the earliest available form of the text is. That’s the language the scholars use, the earliest available form of the text. And yes, it’s true, based on the surviving evidence we have, we can get back to what looks like the earliest form of the text. That’s not the same thing as what Dan is calling the original text. Even the scholars in Germany that he’s talking about have admitted quite clearly that when they talk about reconstructing the earliest form of the text, what they call the “initial text”, that it might be significantly different from the text that the author produced. So, yes, we agree on attaining the earliest form of the text, what we don’t agree on is the original text.

Dan has asked me two questions. Can I come up with a scenario to explain how a text has disappeared without a trace.

This is a softball. Look, the Gospel of Mark, suppose Mark was done in Rome sometimes around the year 70, somebody wrote something that we call the Gospel of Mark. Suppose it was copied twice, by scribe A and scribe B. Scribe A was obscure and his copy got lost. Unfortunately he was a very accurate copier. Copyist B was not a very accurate copier and he made a lot of mistakes but he was a well liked guy and everybody knew about his copy and his copy got copied five times. And then that… those five copies each got copied ten times. And then those fifty copies each got copied another ten time. You’ve got 500 copies all going back to B which was filled with mistakes and the accurate copy is lost. So it’s completely possible that that copy, copy B, has incorporated a mistake that got transferred to all of the surviving copies. So I mean it’s not hard at all to imagine a scenario where that happened.